What a difference a millennium makes. Back in the 20th Century, the United States seldom sold any dairy products to customers or consumers across the border or beyond the pond. And about the only products that did make the trip to overseas destinations were either given away or heavily subsidized.

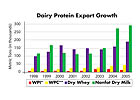

Last year, U.S. producers and manufacturers moved 8.3% of the milk produced in the USA to customers located beyond our borders; most of it commercially, i.e. sans government subsidies.

It didn't really take a millennium to make this giant stride. It just took about five years on either side of the demarcation line. Back in the mid-1990s, this country's milk producers (via Dairy Management Inc.) and several manufacturers, broker/distributors and their suppliers joined ranks to create the U.S. Dairy Export Council (USDEC).

Fast-forward to 2005. U.S. dairy products worth $1.66 billion were sold abroad. In fact, last year was the sixth consecutive year that sales topped $1 billion. Dollar sales were boosted, of course, by milk prices that were the third highest ever in the United States. That's what makes the story even more incredible.

Domestic prices don't drive exports; international prices do. During three of the past four years, domestic prices have been either the first, second or third highest on record. And, around the world, prices have also been relatively high. Right now, international prices are actually higher than U.S. prices for some products.

Several recent research studies have reached a similar conclusion: For the next five to ten years, worldwide demand for dairy products will increase about 2% annually; however, the supply of milk and dairy products will only increase about 1%. A supply-demand such as this simply spells firm to higher dairy prices for another decade.

A sharp reduction in export subsidies has also contributed to the rise in dairy product prices. During 2003, the latest data available, the European Union paid subsidies on 28% of the cheese, 19% of the skim milk powder and 31% of the butter exported. In other words, the government covered the spread between relatively high EU prices and lower world prices, thus enabling the EU to make international sales.

EU treasuries have been figuring out that they can no longer afford to spend billions of dollars on export subsidies. Bottomline: Subsidies have been reduced and world market prices have moved higher.

Critics and pessimists have long argued that the U.S. could never be competitive in the world market. Our products were simply too expensive. Not so. During 2005, 95% of the U.S. exports moved in the international market without subsidies. As recently as 1995, about half were subsidized. This reversal is the direct result of stronger international demand, limited supplies and reductions in export subsidies.

Driving exports takes a commitment to the marketplace, just as it does domestically.

Jerry Dryer was a featured speaker at the 2006 International Cheese Technology Exposition April 27 in Madison, Wisconsin. His talk was "Trends for Truly Novel Cheese Ideas and Market Penetration."