All kidding aside, ice cream freezers and hardeners are marvels of frigidity. Spiral freezers, tray and tunnel hardeners produce arctic-like -30 degree C temperatures, complete with windchill. And the continuous freezers used to manufacture the ice cream are getting colder too. While most operate in the -6 degree C range to bring the liquid and dry ingredients to a semi-solid state similar to soft serve, one manufacturer is introducing a new model that operates at -12 to -15 degrees C which is especially advantageous for low fat and fat-free products.

Additionally, trends toward more complex ice cream formulations, with multiple dry ingredients, has led to more integration of continuos freezers and other equipment components says, Gustav Korsholm, managing director of Tetra Pak Hoyer.

"Years ago you had only a few SKUs where they had more than one ingredient.," Korsholm says. "Today you have two or three dry ingredients and a variegate. And you want to make sure that all of them are in each of the containers."

Components are now designed so that fruits feeders and variegate feeders and continuos freezers can all be stopped and started, in the right sequence, at the push of a button.

As with nearly all dairy equipment, freezers lines have evolved to included larger, faster machines with capacities of up to 1,000 gals an hour. More sophisticated electronic controls allow for automatic set up and changeover for multiple SKUs and more automated operation with tighter QC tolerances. These levels of control sophistication have gradually migrated to smaller, lower-price units. Today's continuos freezers operate on a smaller charge of Ammonia, and some smaller units chill by way of Freon.

At last month's Worldwide Food Expo, Hoyer introduced a new freezer that operates at lower temperatures. Korsholm says early indications are that the new machine will provide a number of benefits related to smaller ice crystal formation.

"It really enhances the creaminess of the product, especially for water ice, low-fat and fat-free," he says. "Also, it gives you a product that is not as sensitive to temperature changes in the distributions system."

The company also notes that the low-temperature filling can allow a manufacturer to bypass the use of a hardening tunnel, and offer some cost savings by way of richer products at lower fat levels.

Hardeners and tunnels

In most applications, ice cream needs to be hardened in a tunnel, tray or spiral hardener. Each takes a different approach to the same need-getting the packaged ice cream to a hard-frozen state in about one to five hours.Again, thanks to better control electronics, today's hardeners are able to do more.

"They can be set up for variable retention, and we can keep better track of products and accept products from multiple lines," Korsholm says. "They can even keep track of what's on each tray and send the correct mix of products to an automated palletizer."

In general, package size and output rates determine what kind and what size of hardener is used. Secondary packaging configurations also come into play, as manufacturers must decide whether to bundle or wrap the packages before or after hardening. Products that are bundled and wrapped generally take longer to harden than free cartons.

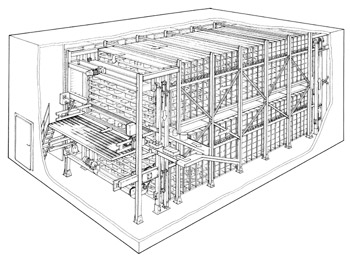

Large bulk operations like Marigold Foods' plant in Rochester, Minn. use massive tray hardening systems that bring ice cream from several lines (at Rochester there are five) and stage it on a series of trays that are rotated throughout the cold, insulated room, sometimes in a carousel fashion.

Spiral freezers on the other hand employ large drums with continuos circular conveyors that gradually lift containers up through a cold environment. In some applications a single-spiral configuration sends the ice cream out of the top of the unit when it is finished, and in others a double spiral is utilized so that the product is taken up and them brought back down.

Because they use vertical space, the spirals are have a smaller footprint than tray systems and are ideal for landlocked facilities and other instances where floor space is hard to come by. But due to their reliance on vertical space, they usually aren't practical for bulk tubs.

But at Ben & Jerry's newly expanded plant in St. Albans, Vt., a double spiral manufactured by Northfield is used for 2.5 gal bulk boxes and can also be used for pints or 3 gal rounds our just about anything in between.

"You have to have a height that will allow that," says Ben & Jerry's dir. of manufacturing Drake Wallis. " You also have to be able to have it come out frozen."

So when the inclusion kings began consolidated operations late last year, a spiral was built into the addition at St. Albans. The unique square boxes, bound for Ben & Jerry's scoop shops, have been passing through the big spiral since April.

"We had a tray hardener in Springfield that really wasn't big enough" Wallis says. "We were trying to get lines speeds a little better, and we decided that we could run 15 tubs a minute and have it come out with a core temperature of zero."

The boxes spend about 8 hours in the 35-foot tall spirals.