Home » Keywords: » frozen dessert processing

Items Tagged with 'frozen dessert processing'

ARTICLES

The creation of ice cream-like functionalities and sensory appeal involves new challenges on multiple fronts

Read More

Using ‘rare’ sugars in ice cream, frozen dessert formulas affects everything

Using ‘rare’ sugars in ice cream and frozen dessert formulas affects everything from nutrition labeling to processing considerations, like the freezing point depression.

September 7, 2016

Using ‘rare sugars’ in frozen dairy and nondairy desserts

In this first of two parts, the authors discuss ‘rare sugars’ and their application in frozen dairy and nondairy desserts.

May 9, 2016

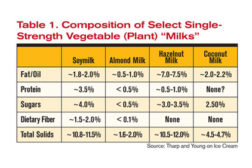

Creating frozen desserts with nondairy milks

Formulating with plant-based milks is not as straight forward as simply substituting dairy milk with an alternative. Here’s what you need to consider.

May 10, 2014

Get our new eMagazine delivered to your inbox every month.

Stay in the know on the latest dairy industry trends.

SUBSCRIBE TODAYCopyright ©2024. All Rights Reserved BNP Media.

Design, CMS, Hosting & Web Development :: ePublishing