The ways in which today’s ice cream entrepreneurs accomplish that mission are as many and varied as the companies themselves. Snoqualmie Gourmet Ice Cream of Lynnwood, Wash. (just north of Seattle) features a Jack Daniels flavored ice cream one of about 600 flavors in its repertoire. Moxley’s Homemade Ice Cream in Towson, Md., is known for what the owner calls mojo ice cream (made with crushed Oreo’s) and Old Bay (flavored by the crab-seasoning characteristic of the Chesapeake Bay region) ice cream. Moxley, by the way, is owner Tom Washburn’s dog, and you can find a picture of him on the company’s website.

Sonny’s Ice Cream of Minneapolis prides itself on using the finest ingredients and buying only local, organic cream and milk. “We’ve been to our suppliers’ farms in western Minnesota, and we’ve seen that their cows eat better than most humans do,” says owner Ron Siron, with perhaps a touch of hyperbole.

Shatila Food Products in Detroit has thrived by featuring flavors and ingredients from India. Whatever their tack, these and many other like-minded firms are establishing a significant presence in their local area’s super-premium market. (And in some cases, beyond Sonny’s sells in Chicago while Snoqualmie is actively plotting its entry into the Portland, Ore. market.) These companies are making ice cream for ice cream lovers, who will gladly pay $3.50 or more for a pint of creamy, dense product, rather than $1.75 for the same amount of a mass-marketed brand.

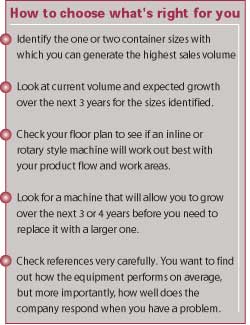

But the rapid growth enjoyed by many small ice cream manufacturers presents a whole new set of challenges. Perhaps none is thornier or more critical to a company’s future than when and to what extent they ought to automate production and packaging.

Sometimes it can be a matter of absolute necessity. Firms may experience such fast sales growth that they simply cannot get the job done by hand any longer. Snoqualmie owner Barry Bettinger points out that his company has averaged 30% a year growth in sales over the six years he and his wife have owned the firm.

Sonny’s owner Ron Siron (Ron’s father, Sonny, started the business in 1945) says for a long time the company packed all its pints by hand. The same was true of the 4-oz containers the company supplied for Northwest Airlines flights. “After you’ve cut a couple million wedges of ice cream, you start to think there’s a better way of doing it,” Siron says ruefully.

Smaller ice cream makers may actually find themselves turning down new accounts because of an inability to fill the orders. Hiring a few extra employees alone won’t necessarily do the trick, because the job of filling the containers especially the pint-sized or smaller cups most gourmet ice creams fanciers fancy is so labor-intensive.

The tougher challenge is filling the containers and placing the lids. If done by hand, both jobs are labor-intensive and time-consuming. It’s not a problem to make the ice cream, but getting it into small cups is difficult.

The first step for many companies may be getting a table top piston depositor. To operate this machine, a worker holds a cup under the fill nozzle and then depresses a foot pedal which through the stroke of a piston injects the desired volume of product into the container. That’s instead of simply using a ladle to scoop the product into a cup by hand.

T.D. Sawvel of Maple Plain, Minn., makes a piston depositor that may cost in the neighborhood of $5,000 to $6,000. Cup size can be adjusted from four ounces all the way up to 190-oz containers. Tindall Packaging of Vicksburg, Mich. is another equipment manufacturer with its own full range of offerings. Waukesha Cherry-Burrell in Delavan, Wis., also manufactures production and packaging machinery for the ice cream industry.

Another alternative is leasing: such a machine may be rented for about $175 a month from a number of companies, including Sawvel and the Sweetheart Cup Co. in Owings Mill, Md.

Further levels of automation can be achieved incrementally or all at once. The former approach might involve adding a lidder to the piston depositor. The lidder places and seals the lid. This step might cost a further $6,000.

A completely automated line from T.D. Sawvel cup dropping, indexing (moving the cups to where they’re to be filled), filling, and lidding would likely cost upwards of $25,000.

Choosing the proper degree of automation is not the only issue to be resolved. Ice cream makers going up the automation ladder may find they will need more storage space, which means expanding their freezer or cold storage areas. They may need a bigger air compressor to run the machine. There can also be other associated infrastructure costs. The bigger companies may need some type of conveyor system to move the product from the packaging machine into the freezer.

Another issue is maintenance. Ice cream packaging equipment can work for a long time some machines installed by T.D. Sawvel in 1977 are still operating. But even the best designed and maintained machines need proper care and handling.

Ron Siron of Sonny’s Ice Cream purchased a complete system from Sawvel that fills, lids, and seals the lids for about $30,000. While he says it has met his company’s needs very well, there are still occasional problems. When that occurs, he says, typically the manufacturer is able to walk him through the problem so he can resolve it himself.

Moxley’s owner Tom Washburn says he’s using a piston depositor filling machine bought from T.D. Sawvel. Partially automating the packaging process has been a big factor in Moxley’s growth. Washburn started the company in 1998 as a single ice cream parlor and a 20-gal batch maker in the basement. Now he’s got three stores and an 8,000 sq. ft. factory in nearby Baltimore, and he’s supplying 2-gal tubs to area restaurants and pints and 8 oz. containers to grocery stores.

Washburn says he’s thinking about purchasing a label applicator and another machine that would enable him to modify pre-printed labels so that it becomes easier to satisfy legal labeling requirements when he changes flavors.