The framework for American dairy product exports has painstakingly been established over the last decade by various U.S. dairy processors and trading companies, as well as the U.S. Dairy Export Council (USDEC). At the time USDEC was founded in 1995, stateside dairy interests were roundly criticized as being 30 years behind competitors from European and Oceania countries, reports Tom Suber, USDEC president.

"We've narrowed that gap considerably over the last decade," Suber says. "Though we've still a long way to go, we've established a U.S. presence in most major markets by demonstrating our reliability as a supplier of a wide variety of high-quality dairy products to meet customers' needs. Our ongoing growth of unsubsidized product sales is just one indication the U.S. dairy industry has come of age in the export market."

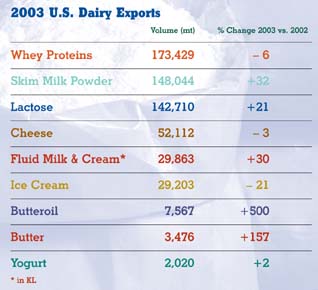

Case in point: In 1995, subsidized milk powders and butter accounted for 44% of U.S. dairy exports. In 2003, only 22% of U.S. exports were subsidized. Milk powder is still a prominent export category, but now it's joined by higher-value products like whey proteins, lactose, cheese, fluid milk and ice cream (see accompanying charts). Furthermore, total dairy exports have topped $1 billion four years running, and are poised to establish a new high in 2004.

Davisco Foods International Inc., Eden Prairie, Minn., entered the global whey protein market more than 20 years ago by establishing overseas offices, and was instrumental in developing the market in Japan. "We've always operated in a market that doesn't require any subsidies. You can get the business, if the pricing is there," says David Curta, Davisco's international sales manager. Today, the major U.S. exporter of whey products focuses R&D and marketing efforts on milk proteins for use mainly in infant formula, sports nutrition and functional food/nutraceutical products.

"The only infrastructure for international dairy business is found in USDEC," notes Ted Jacoby Sr., president of St. Louis, Mo.-based T.C. Jacoby & Co. Inc. "They have done a good job of putting together a bi-partisan, cross-industry consortium of players-traders, co-ops, processors, proprietary handlers-to lay the groundwork for the day when we move international. Setting up the infrastructure correctly is critical to success. It's not just a slam-dunk," he says. The trading firm moved into the international trade arena about 10 years ago, and exports fluid milk, cheese and other products to Mexico and Canada.

Investments in overseas offices combined with product improvements and growing international whey protein markets have made U.S. players a much more viable part of global multinationals' supply base. Though trading companies do a good job of promoting U.S. products abroad, Davisco is committed to maintaining first-hand contact with end users.

"It's an opportunity for the U.S. manufacturers to really understand what a new market is looking for," Curta says. "You get better returns with personal contact, rather than relying on phone, fax and e-mail. Most of the buyers, particularly China, really want to know the manufacturers and work with them, and don't want too many intermediaries involved."

Competing in the international dairy market remains difficult, but is no longer impossible.

"One of the important changes in the international dairy industry and U.S. dairy exports over the last decade is that U.S. suppliers now see international customers as valued and continued customers, rather than as a means or place to dispose of surplus inventory," says Jim Geyer, vice president of the ingredient division of Foremost Farms. The Baraboo, Wis.-based cooperative markets and customizes its whey products for use in food and feed product applications around the world.

Home & Abroad

While the progress outside our borders is encouraging, some exporters believe U.S. exports would be even more successful if not for the constraints of domestic U.S. dairy policy and inequitable global trade rules. Beyond policy, domestic demand can limit the supply of product for overseas sales and leave little room for globally competitive pricing.As relative latecomers to the world market, U.S. dairy exporters work with domestic policies that were implemented -- and international agreements that were negotiated -- before the industry took a global view.

For example, the Dairy Export Incentive Program (DEIP), America's export subsidy allowance, is capped at 68,201 metric tons of skim milk powder, 3,030 tons of cheese and 21,097 tons of butterfat per year, while the EU is allowed to subsidize exports of 273,000 tons of skim milk powder, 321,000 tons of cheese, 399,000 tons of butterfat and 958,000 tons of "other products." Those limits were negotiated more than 10 years ago during the GATT world trade round. Meanwhile, domestic policies such as those supporting U.S. government purchases of surplus milk powder can hamper the expansion of international business.

Working within the framework of the World Trade Organization's negotiations, domestic industry leaders are striving to level the playing field for U.S. exporters. Reform of international trade rules won't come about overnight, and industry negotiators are cautious about across-the-board multilateral reforms. Changes to the U.S. approach without changes of equal impact to the systems used by competitors carry the risk of "hanging our dairy farmers out to dry," Geyer says.

When world players drop agriculture export subsidies and provide more open market access, the U.S. dairy industry will be in a more price-competitive position that will complement its quality and service. Since 94% of the U.S. milk supply is consumed within its borders, product availability and regulatory barriers can forestall efforts by U.S. manufacturers to become globally competitive, exporters say. The same world trade agreements that set inequities in global export subsidies also established the current tariff-free import of products like MPCs, making them cheaper to import than to produce in the United States.

Domestic dairy market performance-including demand and selling prices at home-will continue to influence U.S. dairy export performance, effort and product availability. "When the domestic price is higher and demand is strong, it is difficult to continue to supply product for export at a lower price. It requires development of less price-sensitive products and recognition that in the long run, export sales are one of the reasons the domestic price remains strong," Geyer says.

And it's in the long run, USDEC officials point out, where the rewards will come. When exporters work to provide international customers with reliable and consistent product supply, even through tight supply times, their buyers will return that commitment when supplies ease up and U.S. products are more widely available.

The domestic market's extreme swings in butter and cheese pricing also affect U.S. ability to grow exports. "No other country in the world experiences the volatility we do in milk prices. We cannot compete globally unless we can provide high quality products at relatively stable prices on an ongoing basis," Jeter notes.

Meanwhile, some U.S. farm interests are teaming up with international players, such as the partnership between mega-cooperatives Kansas City, Mo.-based Dairy Farmers of America and New Zealand's Fonterra Cooperative Group Ltd. In the current climate, such arrangements can help U.S. dairy businesses get accustomed to the market. But some warn against future conflicts of interest in partnering with a U.S. competitor.

Export Outlook

As international barriers to trade continue to erode, the forecast for U.S. dairy product sales abroad brightens. The global market perception of U.S. dairy offerings continues to improve. International sales of high-value, commercial American products like table and foodservice cheeses, lactose, and whey protein concentrates continue to grow, and are considered crucial to the long-term health of the U.S. dairy industry.Mexico, Japan, Southeast Asia, Canada and China are major buyers of U.S. dairy products. "The U.S. dairy industry produces 50% more whey and twice as much lactose as the domestic market can absorb," Suber notes. "If we were not able to move these products into overseas markets, the U.S. would have a serious surplus of milk solids."

While the perception of U.S. dairy product ingredient quality previously lagged behind the reputation of European offerings, a shift has occurred. As health and sanitation challenges hold global dairy ingredient manufacturers to higher standards, the U.S. dairy industry's claim to the most stringent performance requirements in the world is a distinct selling point, exporters agree. "The world market now knows that our products are very good, and very consistent," Curta explains.

U.S. cheese production creates numerous companion products valued as ingredients that meet the functional and nutritional needs of end-users. Agri-Mark, Inc., Lawrence, Mass., for instance, offers cheese derivative ingredients include whey protein concentrate, sweet whey, dairy product solids (whey permeate) and lactose. High-value whey proteins are increasingly being used to formulate recombined dairy beverages, nutritional foods, cheese, ice cream, fermented products, infant formula and other foods.

Meanwhile, market access is improving - and paying dividends for exporters.

Top U.S. export markets of the future vary by ingredient and by cultural food consumption practices, but Mexico, Latin America, and Asia top the list. "The United States is going to be hard-pressed to fill the needs of Mexico alone," Jacoby says.

Shortly after joining the WTO and reduced its dairy tariffs, China became the biggest U.S. whey market by volume, up 140% in the last four years. China's growing need for animal feed and consumer dairy goods correlates with its economic growth. Meanwhile, its government health initiatives and recent food safety issues have driven demand for high-quality dairy ingredients.

Already, the tariff for lactose in China is more in line with its whey tariff. And Davisco is bullish about the use of the individual components of whey for recombination of products such as infant formula. "The technology gets better and allows us to do more. Every two or three years, there's a pretty big leap as far as what can be done in the separation process," Curta says. He points to the new ability to create infant formula with major similarities to mother's milk. "If we get can the word out about that, we can change the way a lot of infant formula is manufactured."

As income levels in China and India continue to rise and the sports nutrition industry keeps growing in Europe and Japan, demand for U.S. whey products is expected to increase. Dairy exporting opportunities will follow the changes and improvements in standards of living in developing countries, Geyer says, citing the potential to provide customer need-specific products in customized or blended formats as well as to supply multiple locations of multinational companies.

Application seminars and technical consultations with ingredient buyers in the Far East and Latin America sponsored by USDEC also draw strong industry and local end-user participation, Suber says. "The ultimate result is that these activities allow U.S. companies to form strong buyer relationships, opening the door for expanded usage and new applications by new and existing customers," Suber says.

New Zealand is currently the international leader in dairy exports and enjoys low-cost production, but its growth potential is limited by relatively small amounts of suitable, available land. Australia and the EU round out the dairy export industry's top three players. Other nations, such as Brazil and Argentina, have the potential to expand export capabilities, Suber says. "But at the same time, increasing worldwide demand will strain supply enormously," he notes. "When you add to that the possibility of EU dairy production going increasingly internal as it expands, it's clear that the United States is well-positioned to expand production to meet growing global demand."