How about the increasingly volatile weather, the on-again/off-again global economy and the long-term effects of growing demand in emerging markets, for everything from infant formula to cheese-laden pizzas?

As dairy processors and manufacturers manage in this complex, global environment, all signs point to increased volatility of dairy markets. In fact, managing price volatility has the potential to be such a game-changer that it was identified as one of the seven priority programs in the “Globalization Report” prepared by Bain & Co. and commissioned by the Innovation Center for U.S. Dairy.

Customers confounded by the U.S. market

It’s not always easy being an international player based in the United States. The weekly and monthly contracting at the CME and the cumbersome classified pricing system are head-scratchers to global buyers who are used to 3-, 6- and 9-month contracts.

“Export customers are often confounded and frustrated by the complexity of the U.S. system,” says Kevin Vogt, vice president, Hilmar Ingredients, Hilmar, Calif. “Our export customers face the same challenges that our domestic customers face with developing new products that use dairy ingredients. They are concerned that the long development timeline, the volatility of ingredient prices and the uncertainty of future supply could hamper the commercial launch of value-added products.”

And while offering a NASS-plus price helps to ensure export customers get a competitive deal and processors still can make their margins, it’s nearly impossible to explain.

“When trading internationally, it’s harder to feel good about our ability to set a price point,” says Ken Meyers, president and CEO, MCT Dairies, Millburn, N.J. “I can’t go out and say ‘this is my price’ vs. New Zealand’s price. The U.S. pricing mechanism is archaic and it is an impediment to trade. It forces us to assume a lot of risk.”

“In my opinion, the biggest constraint to the increased use of risk management tools is the regulated pricing systems in the United States,” says Mike McCully, director of dairy procurement, Kraft Foods Inc., Northfield, Ill.

Volatility is a headache and an opportunity

The entire commodity complex has devoted significant brain power dissecting the causes of increasing market volatility. But most agree that understanding why volatility exists is secondary to having a plan in place that addresses the fact that it does exist. That’s true whether you sell your product domestically, globally or both.

And volatility doesn’t appear to be going away, even as emerging trading indices like GlobalDairyTrade (GDT) and futures markets in New Zealand and Europe gain steam.

“The interesting part is there seems to be more transparency than ever due to globalization influenced by the Internet, GDT and mandatory reporting,” Meyers notes. “We’re starting to receive more information, but piecing it all together to create a credible demand situation is not so easy. The better the information, the better we can all manage risk.”

And from the dairy producer standpoint, the lessons of 2009 made demystifying risk management tools jump to the top of their to-do list.

“The risk is squarely on the dairy farmer,” says Marc Beck, senior vice president, market development, U.S. Dairy Export Council, Arlington, Va. “We saw that in 2009. They paid that bill; they paid it here as well as globally. I don’t think we want to ask them to pay it again. We need to concern ourselves first and foremost that dairy producers can stay in business. We should really think strategically about how we’re going to maintain this production domestically. One way to do that is to make sure that our markets help us maintain our business.”

“I think we’re at the tip of the iceberg when we’re going to have an explosion of risk management tools by dairy farmers,” says Ed Gallagher, president of Dairy Risk Management Services, a division of Dairy Farmers of America (DFA), Kansas City, Mo., and vice president of economics and risk management, Dairylea Cooperative Inc., Syracuse, N.Y. “Some are doing it on their own, while others are coming kicking and screaming because their lenders are making them, but there’s record use of futures among DFA and Dairylea farmers this year.”

The numbers bear this out: use of dairy futures and options at the CME Group has expanded dramatically in 2011. At the end of the third quarter, open interest on all dairy futures and options was 146,107 contracts, up 91% from a year earlier. Open interest on Class III milk options more than doubled, Class IV futures contracts spiked this year and take-up of cheese futures is so great, it became the second-most-active dairy futures contract just 15 months after it launched.

Gallagher notes he’s not sure risk management tools are being adopted at the same rate by processors.

“We have members that want to go out multiple years,” he says, but cooperatives often have trouble finding willing partners on the end-user side. “I think there are a lot of end-users out there who are still living in the mid-2000s. I’m hoping they’ll step up and embrace these things like they’re doing on the farm side.”

A higher price floor?

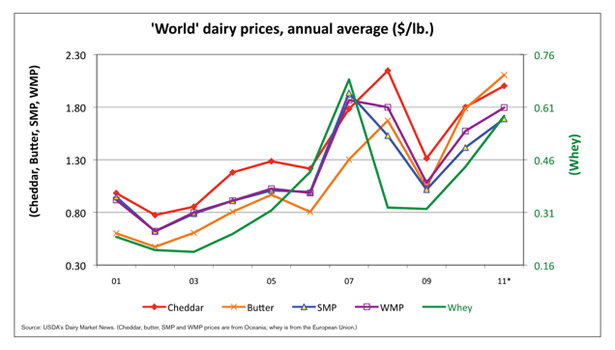

Going forward, strong global markets in 2011 point to a higher price band for dairy products. In the first three quarters of the year, world commodity reference prices were roughly 20% higher than the five-year average for milk powder and cheese, 33% higher for whey and 60% higher for butter.

“We seem to be at a point where the ‘floor’ value of dairy products is just not, on a long-term basis, as low as it has been historically,” says Sara Dorland, managing partner, Ceres Dairy Risk Management LLC, Seattle. “The shock value of the commodity prices has worn off and consumers are not necessarily changing their purchasing patterns due to $1.30 to $1.40 non-fat dry milk values found in their end products — as may have been the case in 2007 or 2008.”

As for whether the recent high prices for dairy products are sustainable, Meyers reminds his clients that what was once difficult to imagine can become routine in a flash.

“We have now gone through that $2 cheese price point on several occasions. Every time you break through a price point, you go through a pattern: First time you cry, second time you wonder and the third time you expect it. Markets have a way of testing price points and elasticity points,” he notes.

“Absent another cataclysmic event (like the complete economic breakdown of 2008-09), we have to realize that we moved that platform up,” Meyers concludes. “We are going to see a higher average price. It’s not going to be over $2 for cheese on a daily basis, but it could be $1.55 or $1.65.”

Either way, the need for viable risk management tools will only intensify. The good news is that U.S. suppliers have about a 10-year head-start in using risk management tools. The bad news is that suppliers from elsewhere are cutting the learning curve quickly. In an expanding, interconnected global dairy market, the stakes are high. For those who understand and contract for the price ups and downs, it can be a genuine competitive advantage.

|

Exporters Are Talking About:

• Managing price volatility |